It has become a truism that we live in a fast-paced world. In less than a century, modern technology has enabled us to convert a planet with a surface area of 197 million square miles into a global neighborhood.

In 1750, for example, it took 4-6 weeks to sail by ship from New York to London. By 1850, with the advent of the steam engine, the trans-Atlantic journey was reduced to around 1 week. Today, we can fly from New York to London in just 8 hours.

This acceleration in travel illustrates a new value that has emerged for us in the modern world: speed. “Time is money,” we are told and the finance report does not lie. The litmus test for the quality and success of an endeavor is how fast we can complete it. For the sooner we can cross a task off our list, the more quickly we can move on to the next task. Then the next task. Then the next task. Only here’s the catch in a knowledge economy: the list is infinite.

In education, this obsession for speed materializes in daily schedules, pacing charts, and lesson plans. We move from subject to subject, concept to concept, and assignment to assignment at the speed of light. But is this approach best for students? Is it cultivating virtue? Are they actually developing mastery over what they are learning? Or are these moments of quick exposure creating the illusion of learning instead?

Festina Lente: Make Haste Slowly

In The Good Teacher (Classical Academic Press, 2025), Christopher Perrin and Carrie Eben argue that it is not. Of the ten principles for great teaching they present in their book, the first is “Festina Lente, Make Haste Slowly.” They propose that instead of engaging in the rush to cover content, it is better to master each step in a lesson, setting a pace that is fitting for the time available.

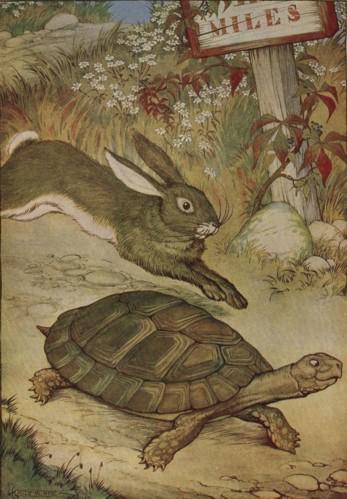

Perrin and Eben go on to provide two examples of this principle in our world today. The first is drawn from Aesop’s beloved fable, “The Tortoise and the Hare.” In this well-known tale, two creatures, a quick-footed hare and a contemplative tortoise, engage in a foot race. While the hare is expected to win with its focus on speed, it is actually the tortoise who wins the race. The upshot is that while the hare was certainly faster, its pace was not sustainable. The tortoise, on the other hand, moves at a slower yet sustainable pace, making haste slowly, and ultimately becomes the victor.

The other example is Jim Collins’ “Twenty Mile March” concept in Great by Choice (Random House, 2011). Imagine two hikers setting out on a three-thousand mile walk from San Diego, California, to the tip of Maine. One hiker commits to twenty miles a day, no exceptions. Whether the conditions are fair or poor, the itinerary is the same. The other hiker adjusts his daily regimen to the circumstances before him. Depending on weather, terrain, and energy levels, some days he may walk 40 miles, other days he may not walk at all. Like the tortoise in Aesop’s fable, the winner of the race is the hiker committed to the wise, disciplined journey, choosing sustainability over speed.

Now, it must be pointed out that every analogy has its limits. Not every speedster struggles with the overconfidence exhibited in the hare or the weak will of the second hiker. It is possible to be both fast and virtuous.The key insight is not that we need to choose between the two, but in our present culture’s emphasis on speed, we would do well to slow down, resist the lure of speedy completion, and focus on a process that will instill virtues of diligence and perseverance.

Connecting the twenty-mile hike example to teaching, Perrin and Eben write,

Classical education can be compared to the long journey in this story. Each segment should be intentional, planned, and exercised wisely, with ample allotted time. Students, like the winning hiker, should use time well, as they are guided and modeled along each segment of their academic journey. (p. 24)

Working at a Natural Pace

Interestingly, Cal Newport, the author of Deep Work, Digital Minimalism, and A World Without Email, is on to a similar idea in his latest book, Slow Productivity (Penguin Random House, 2024).

Newport observes that we as a culture have succumbed to what he calls pseudo-productivity, “the use of visible activity as the primary means of approximating actual productive effort (22). So we work longer hours, send more emails, and complete more projects, all in the name of productivity. The only problem is that we burn ourselves out, ultimately accomplishing less and at a lower quality.

Newport’s solution is to adopt a different philosophy of work, one in which we accomplish tasks in a sustainable and meaningful manner. His three principles for this approach are:

- Do fewer things.

- Work at a natural pace.

- Obsess over quality.

My colleague at Educational Renaissance, Jason Barney, has written extensively on these principles for the classical educator in this blog series. I encourage you to check out all four articles as he interacts with the likes of Aristotle, Quintilian, Charlotte Mason, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyiy, and others.

Regarding our present focus on how to manage time in the classroom for the sake of virtue formation, Jason writes, “There must be a purposeful movement in a meaningful direction at the same time as a willingness to delay over the details to ensure quality and a student’s developing mastery. Great teachers can discern when to slow down and when to hasten on.”

Rather than sending students off to work on a frenzy of assignments at once, moving from one worksheet to the next, it is better to slow down and hone in on one worthy assignment that will lead students toward a greater depth of understanding.

True Mastery: Getting the Practice Right

Here we come to a key distinction that must be made. Thus far, I have been encouraging teachers to focus on virtue over speed, process over outcome, and mastery over pseudo-productivity. But what does true mastery look like? And how is it achieved?

I suggest that mastery is achieved when a student can repeatedly demonstrate a particular skill or lucidly explain a concept on demand. In The Good Teacher, Perrin and Eben are adamant that until this happens, teachers should not move on to the next objective, whether it is moving on from addition to multiplication or 3rd to 4th grade (21-22). They are also careful to identify a distortion of festina lente, namely, using the principle as an excuse to focus too long on one concept at the expense of others (27).

The key clarification I want to make as we seek to implement a mastery-focused approach is regarding the type of practice we ought to implement to meet this end. It would be natural to assume that if the focus is mastery, teachers should engage in what is called massed practice: practice over and over a specific skill until it is mastered, and only then move on to the next skill. Make haste slowly, right?

In Make it Stick: The Science of Successful Learning (Belknap Press, 2014), the authors draw upon cognitive science to argue that this sort of practice can only take you so far. They seek to dispel of the myth that the focused, repetitive practice of one thing at a time is the way to mastery.

They write:

If learning can be defined as picking up new knowledge or skills and being able to apply them later, then how quickly you pick something up is only part of the story. Is it still there when you need to use it out in the everyday world?…The rapid gains produced by massed practice are often evident, but the rapid forgetting that follows is not. (p. 47)

Interestingly, the authors of Make it Stick are putting their finger on the same concern as Perrin and Eben: prioritizing speed over mastery. Instead of practicing one skill over and over again until students can demonstrate mastery, they suggest mixing up the practice.

In a past article, I write more about this topic, unpacking three key ways from Make it Stick to practice toward mastery:

Spaced Practice: Instead of intensively focusing on one skill for a single, extended session, space out the practice into multiple sessions. Work on it for a while and then return to it the next day or week. The space allotted between each session allows for the knowledge of the skill to soak into one’s long-term memory and connect to prior knowledge. Revisiting the skill each session certainly takes more effort, but that’s the point.

Interleaved Practice: While we experience the quickest gains by focusing on one specific skill or subset of knowledge over a period of time (momentary strength), interleaving, or mixing up the skill or concept you are focusing on in a practice session, leads to stronger understanding and retention (underlying habit strength). It feels sluggish and frustrating at times, for both teachers and students mind you, because it involves moving from skill to skill before full mastery is attained, but it leads to both a depth and durability of knowledge that massed practice does not (50).

Varied Practice: Varying practice entails constantly changing up the situation or conditions in which the skill or concept is being applied. It therefore strengthens the ability to transfer learning from one situation and apply it to another, requiring the student to constantly be assessing context and bridging concepts. Because this jump from concept to concept triggers different parts of the brain, it is more cognitively challenging, and therefore encodes the learning “…in a more flexible representation that can be applied more broadly” (52).

To be clear, these forms of mixed practice will be more difficult for students and the practice sessions will take longer. But that is the point. To “make haste slowly” when it comes to practice, you want to support your students in meaningful practice that will lead them toward long-term, not temporary, mastery.

Conclusion

As classical schools, we are playing the long game as we seek to instill wisdom and virtue in our students. In our fast-paced world, this commitment will surely be misunderstood. We are told that a school’s effectiveness ought to be measured by the number of students enrolled, the number of accolades of its graduates, and the impressiveness of test scores.

But if our goal is true mastery for a life of virtue, instilled with the principle of festina lente, then we need to think more like the tortoise than the hare. We need to be intentional with practice, focus on depth over breadth, and mix it up in order to strengthen the durability of the knowledge gained. This is no doubt the harder road, but with our own perseverance at work, we trust that over time it will bear much fruit.

Leave a Reply